|

|

|

#1 |

|

All the news that's fit to excerpt

Name: newsie

Location: who knows?

Join Date: Jun 2008 Motorcycle(s): only digital replicas Posts: Too much.

|

[ridermagazine.com] - Alaska Motorcycle Ride: Discovering America?s Last Frontier

It wasn’t that she was a princess. She had lived and taught on a reservation in northern Ontario where she gutted geese, chopped down trees, and drove on the ice roads. But by her own admission, my partner, Steph, was a sun ‘n’ sand type of vacationer. Riding and wild camping with no electricity was […]

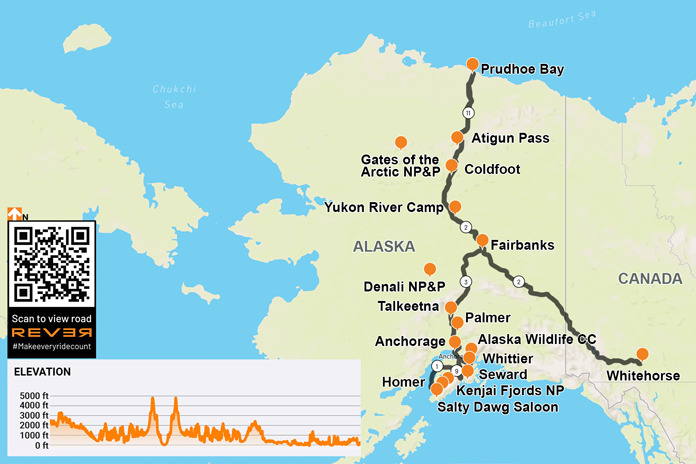

The post Alaska Motorcycle Ride: Discovering America’s Last Frontier appeared first on Rider Magazine.  On the Dalton Highway, Sukakpak Mountain rises 4,390 feet and reflects in the Koyukuk River. Sukakpak is an Iñupiat word meaning “marten deadfall” because, seen from the north, the peak resembles a carefully balanced log used to trap marten. (Photos by the author) On the Dalton Highway, Sukakpak Mountain rises 4,390 feet and reflects in the Koyukuk River. Sukakpak is an Iñupiat word meaning “marten deadfall” because, seen from the north, the peak resembles a carefully balanced log used to trap marten. (Photos by the author)It wasn’t that she was a princess. She had lived and taught on a reservation in northern Ontario where she gutted geese, chopped down trees, and drove on the ice roads. But by her own admission, my partner, Steph, was a sun ‘n’ sand type of vacationer. Riding and wild camping with no electricity was not her idea of a good time. And a hostel? Forget it. So when the opportunity arose for an Alaska motorcycle ride – taking my Suzuki V-Strom 650 from Niagara Falls to America’s last frontier – my suggestion that she fly to Anchorage and meet me…well, it wasn’t flying.*  Built by the U.S. Army for defense from the Japanese in WWII, the Alaska Highway opened the secluded northwest to travel and trade. In the background, the only wooden grain elevator remaining in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, reopened in 1983 as an art gallery. Built by the U.S. Army for defense from the Japanese in WWII, the Alaska Highway opened the secluded northwest to travel and trade. In the background, the only wooden grain elevator remaining in Dawson Creek, British Columbia, reopened in 1983 as an art gallery. But over the weeks – and from over my shoulder – the more she saw of my reading and planning and YouTube videos, the more curious she became. Related: An Alaskan Motorcycle Adventure How-To My late June ride across the Canadian prairies and into northern British Columbia had been an adventurous mix of wind and rain and heat so unbearable that I spent a full day in a rundown Saskatchewan hotel to recover in air-conditioned bliss. But it wasn’t until I reached the Alaska Highway west of Haines Junction, Yukon, that I began to wonder if my riding skills would be up to the task.  Scan QR code above or click here to view the route on REVER The entire 200 miles to the Alaskan border was a constantly changing mix of gravel, chipseal, and potholes, with just enough pavement to inspire complacency. Most disconcerting were the unannounced depressions caused by permafrost. Without warning, the bike would simply drop away beneath me, only to come pounding back like an unbroken bronco. Twice I was certain I was going over the handlebars. Almost as unnerving were the lengthwise ridges that attempted to grab my tires and toss me off the road.  The Alaska Highway threads its way between Kluane Lake and the Kluane Mountains near Destruction Bay, Yukon. The entire 200 miles from Haines Junction to the Alaska border was an adventure in itself. The Alaska Highway threads its way between Kluane Lake and the Kluane Mountains near Destruction Bay, Yukon. The entire 200 miles from Haines Junction to the Alaska border was an adventure in itself.Between the irregular road surface and the wildlife, I was in no danger of nodding off. At one point, I was negotiating a corner on the loose surface when a large moose bolted into my path from the alders on my right. Brakes were almost useless in the gravel. She was so startled that she was still peeing as she charged in front of me, and I admit I checked myself for the same once she had disappeared into the brush. It wasn’t long before I encountered a grizzly and then a caribou on the shoulder, but they at least seemed content to stay put.  Wild camping on the Top of the World Highway near Poker Creek, Alaska. Wild camping on the Top of the World Highway near Poker Creek, Alaska.The pavement improved measurably near Tok. In Yukon River Camp, where I fueled up for the long ride on the Dalton Highway to Prudhoe Bay – one of the “most dangerous roads in America” – I partnered up with another solo rider for mutual support should the trip go (quite literally) sideways. With no shoulder and with roadsides that often plummet 50 feet to the soggy tundra, one of the greatest dangers of the Dalton is unexpectedly becoming the focus of a search party. But the weather gods smiled on us. A sprinkling of rain the day before had dampened the notoriously blinding dust without creating the slippery, muddy mess I had feared. And I marveled at the midnight sun, which kept temperatures between 35 and 60 degrees.  While camping on the Top of the World Highway near Poker Creek, Alaska, the author was awakened by an enormous herd of Porcupine caribou passing by. While camping on the Top of the World Highway near Poker Creek, Alaska, the author was awakened by an enormous herd of Porcupine caribou passing by. After a night of primitive camping – and a surprisingly good meal – in Coldfoot, my riding partner and I spent a full day navigating the dirt and ogling the views: from the omnipresent Trans Alaskan Pipeline to the enormity of the Brooks Mountain Range and Atigun Pass, to the endless sweep of tundra on the North Slope toward the Arctic Ocean. And of course, the muskoxen we encountered as they munched on moss and lichens. Needless to say, high-fives and a toast were in order two days later when we successfully returned to Fairbanks. This was adventure on a new scale.  Just east of the Dalton Highway (aka the “Haul Road,” which runs from just north of Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay), muskoxen roamed the windy tundra of the North Slope near the Sagavanirktok River. They live naturally only in the Canadian arctic tundra, Alaska, and Greenland. Members of the goat family, their underwool is eight times warmer than sheep’s wool yet surprisingly light. Just east of the Dalton Highway (aka the “Haul Road,” which runs from just north of Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay), muskoxen roamed the windy tundra of the North Slope near the Sagavanirktok River. They live naturally only in the Canadian arctic tundra, Alaska, and Greenland. Members of the goat family, their underwool is eight times warmer than sheep’s wool yet surprisingly light. Rolling into Anchorage, on the other hand, I was struck by how much the city was like any other. In fact, locals joke that the best part about Anchorage is that in under an hour, you can drive to Alaska. I searched out the House of Harley-Davidson, which offers riders free camping (including restrooms and showers), and awaited Steph’s arrival.  The Trans Alaska Pipeline runs 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, a port near the Gulf of Alaska, and was engineered to shift with the permafrost, withstand forest fires (as it has done here), and adapt to temperature changes of 180 degrees F (the pipeline lengthens by almost 6 feet in summer heat). The Trans Alaska Pipeline runs 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, a port near the Gulf of Alaska, and was engineered to shift with the permafrost, withstand forest fires (as it has done here), and adapt to temperature changes of 180 degrees F (the pipeline lengthens by almost 6 feet in summer heat).It was a little discouraging the next morning when her flight brought with it a cold front full of clouds and rain. But I was grateful she had come and determined to make the most of our 10 days together. On the way to Flat Top Mountain for a panorama of the city, we rolled along Cange Street, which doubled as an airport runway. Each home had its own attached hangar, and prop planes were parked on several front lawns. On another city corner, we encountered a moose that casually browsed a willow before sauntering across a driveway and into a backyard.  Staring down the Dalton: Is that a smile or grimace? Staring down the Dalton: Is that a smile or grimace? South of town, the Seward Highway hugged the narrow shore between the steep Chugach Mountains and the churning waters of Turnagain Arm. At Beluga Point, we paused to watch the tidal bore, a daily surge of seawater that can be over 3 feet high and sounds like a freight train. The tides themselves, rising to 35 feet, rival those of the East Coast’s Bay of Fundy. Naturally, we had to visit the nearby Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center where injured animals are rehabilitated. It was one place where we were guaranteed to see most of Alaska’s wildlife up close.  Seward Boat Harbor, on Resurrection Bay, is merely an introduction to the beauty in store on the Kenai Peninsula. Seward Boat Harbor, on Resurrection Bay, is merely an introduction to the beauty in store on the Kenai Peninsula.Believing that my intrepid partner deserved at least one nice hotel, I had booked a “glacier view” suite in the port of Whittier. This came with the bonus of riding through North America’s longest tunnel, a single-lane route that runs 2.5 miles under an entire mountain. Besides a fish-processing plant, however, Whittier has only two large buildings, both of which are remnants of World War II: an abandoned military supply post and an apartment building that houses nearly the entire town’s population. Without even a pretense of renovations, the top floor now serves as a hotel. Our apartment, while clean, was clad in 1960s paneling, and the bathroom was adorned floor-to-ceiling in pink tile. Most bizarre was the multitude of safety bars (I counted 10) fastened to the wall in the shower. Steph had started calling it the “Bates Motel,” and I suggested the handles were for grabbing when Norman dropped by. On top of that, not only was the rain incessant and obscured the view of the harbor from our window, but when we asked about the glacier, we were told we’d have to sail 6 miles out of port and around a mountain to get a glimpse. Alaskans also joke that “Everything is sh*ttier in Whittier,” and we just had to laugh.  Wading into the icy waters of Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Ocean. Wading into the icy waters of Prudhoe Bay on the Arctic Ocean.However, if our night had been a low point, the next morning was a decided high. Wearing our raingear and carrying a set of hiking poles, we set out to explore Byron Glacier. Dense forests gave way to alder thickets that soon opened to lichen-dotted boulders. Under a steady rain, we climbed the rugged upper valley where ice lay covered in black silt. Towering high above, the jagged peaks were trimmed in white fondant while sinuous waterfalls tumbled from the sheer cliffs. Ahead, shining and motionless, the bright blue glacier stood before us, a frozen river imperceptibly carving out the valley floor. Dwarfed in this vast, timeless amphitheater, we seemed no more than fleeting specks, and tears welled up in Steph’s eyes. This was travel on a new scale. After a cozy night in a warm log cabin, we continued to Seward where we joined a day-long boat tour of Kenai Fjords National Park and Resurrection Bay, a rich marine ecosystem with craggy coves, deep fjords, and tiny treed islands. Every wildlife sighting brought a new gasp: Sea lions, otters, puffins, murres, and mountain goats were but a prelude to the humpbacks, fin whales, and orcas. Bald eagles watched us from branches along the shore.  Approaching Atigun Pass from the north on the Dalton Highway, the author pauses beside the Sagavanirktok River. Approaching Atigun Pass from the north on the Dalton Highway, the author pauses beside the Sagavanirktok River.Most stunning of all was Northwestern Glacier at the head of the fjord. As a million tiny ice chunks bobbed around our boat like warning buoys, we drew ever closer and were overwhelmed by its size and the thunderous calving. The splitting columns sent booming explosions reverberating off the cliffs, followed by great walls of ice crashing into the frigid water. We stood gripped in a hallowed silence. Arriving in Palmer the following day, we explored the Matanuska Valley, a region with a surprising claim to fame. Particularly fertile soils and summer days with 22 hours of sunlight produce record-setting vegetables: cabbages bigger than beach balls, carrots the size of small logs, and pumpkins that must be lifted by crane. As one resident told me, “We get just as much sunlight as anywhere else – we just get it all at once.”  The author and his partner, Steph, hiking Byron Glacier. The author and his partner, Steph, hiking Byron Glacier.Along the Knik River, we were introduced to glamping in a huge canvas tent with a queen-sized bed, an upholstered chair, and more pillows than a palace. It was a far cry from my bivy sack – and just what Steph had wanted. Morning was a little brighter as we set off for Homer, a small town on the southwest side of the Kenai Peninsula. Twisting through wooded Cooper Landing and Soldotna, the Sterling Highway turned south and followed the coast along Cook Inlet. From Clam Gulch, we skirted the edge of the cliffs all the way to our destination. When keeping my eyes on the road became impossible, we pulled over and tramped through a field to the precipice, where we could see Sadie Peak across sparkling Kachemak Bay standing in snow-covered glory high in the equally glorious Chugach Mountains.  Northwestern Glacier is one of many photo ops at every turn in Kenai Fjords National Park. Northwestern Glacier is one of many photo ops at every turn in Kenai Fjords National Park. The only thing I knew about Homer was that the Salty Dawg Saloon was perched on the end of a spit. As old as the town itself, the diminutive building has served as a school, post office, railway station, and grocery store. In 1957, it became a saloon, and shortly thereafter, as the story goes, a patron who’d grown tired of waiting for his friend stuck a dollar bill to the wall for him to buy a drink if he ever showed up. The ensuing tradition has resulted in every surface being completely papered in dollar bills. Unable to find room for my own bill, I wedged a Loonie (a Canadian dollar coin) into a picture frame and apologized (equally Canadian) to the bartender for my 76-cent contribution. Thirty minutes east of Homer, we bounced down a rutted dirt road to our accommodations on the Kilcher Family Homestead. In the early 1940s, professor Yule Kilcher left war-torn Switzerland to find peace in the wilds of Alaska, where he and his wife built a log cabin and raised eight children. Living a subsistence lifestyle and clearing fields, the family eventually acquired 600 acres, where they continue to live off the land.  Stellavera’s garden-shed-turned-lodging on the Kilcher Family Homestead. Stellavera’s garden-shed-turned-lodging on the Kilcher Family Homestead. You have undoubtedly heard the music of Jewel, one of the Kilcher grandchildren, and may even have seen episodes of their Discovery Channel series, Alaska: The Last Frontier. One daughter, Stellavera, lives off-grid in a yurt near the cliffs and converted a garden shed into a surprisingly enchanting Airbnb. Enclosed in clear corrugated roof panels and furnished with a queen bed, heater, and lots of books, the structure – and the outdoor shower – gave us stellar views of Kachemak Bay and the ice-glazed mountains beyond. It was spectacular. Before we knew it, we had to return to Anchorage, where I needed to do some scheduled bike maintenance and Steph caught a flight home. The weather had deteriorated the day she arrived, and although it never kept us from the many activities we had planned, we joked that the sun would return the day she left. That is exactly what happened. Under a clear blue sky, I rolled out my bivy again, anticipating the next leg of the journey and happy to have spent 10 days with Steph in a land unlike anything we had ever known. She still loves the beach, of course, but now all she can talk about is when we can go back to Alaska, where wonder is on a new scale.  Fireweed adds vibrant color to the cliffs facing Sadie Peak on the far side of Kachemak Bay near Homer. Fireweed adds vibrant color to the cliffs facing Sadie Peak on the far side of Kachemak Bay near Homer.Alaska Motorcycle Ride Resources

The post Alaska Motorcycle Ride: Discovering America’s Last Frontier appeared first on Rider Magazine.

__________________________________________________

I'm a bot. I don't need no stinkin' signature... |

|

|

|

|

Similar Threads

Similar Threads

|

||||

| Thread | Thread Starter | Forum | Replies | Last Post |

| [ridermagazine.com] - 2023 MV Agusta Dragster RR SCS America | First Ride Review | Ninjette Newsbot | Motorcycling News | 0 | July 25th, 2023 12:23 PM |

| [ridermagazine.com] - Kyle Petty Charity Ride Across America*Returns for 27th Year | Ninjette Newsbot | Motorcycling News | 0 | March 9th, 2023 05:41 PM |

| [ridermagazine.com] - 26th Anniversary Kyle Petty Charity Ride Across America | Ninjette Newsbot | Motorcycling News | 0 | April 20th, 2022 12:00 PM |

| [motorcycle.com] - Schuberth Partners With MotoQuest On Alaska Women’s Ride | Ninjette Newsbot | Motorcycling News | 0 | April 4th, 2014 05:00 PM |

| [motorcycle-usa.com] - MotoQuest Alaska All Ladies Ride June 2014 | Ninjette Newsbot | Motorcycling News | 0 | February 11th, 2014 06:50 PM |

|

|